Building The Khipu Field Guide (KFG) Database

A Counter Counts to a Count:

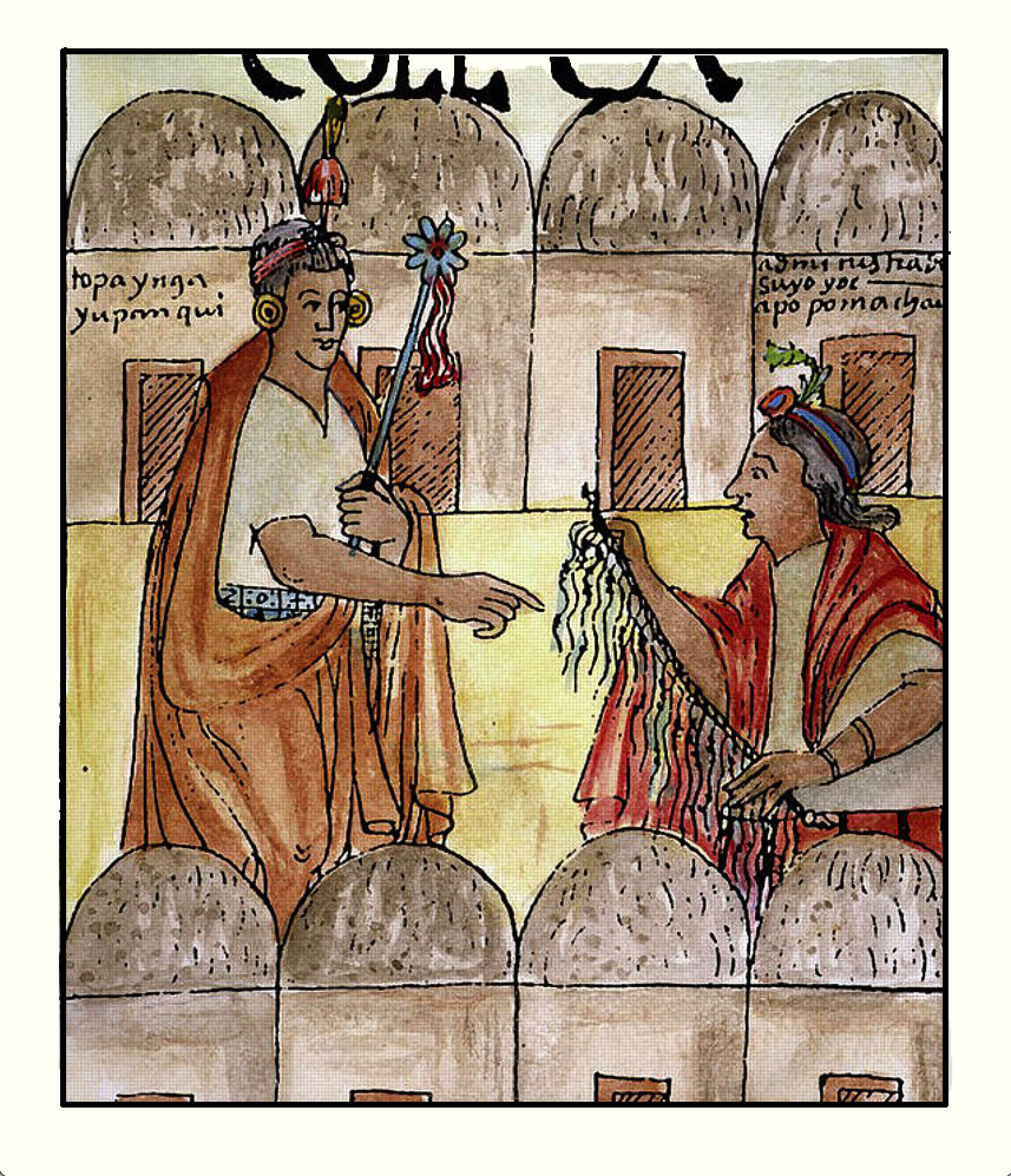

Between 1600 and 1615 A.D, a native Quechua speaking noble, named Felipe Guaman Poma de Ayala, wrote (and drew) a book-length account of native Inka life. He knew Spanish law allowed him to express his grievances of Spanish iniquities in a letter to the court of King Phillip II of Spain. This drawing, subsequently colorized, presents the scene of a khipu-kamayuq (a Khipu reader/maker) reciting a khipu to the Inka emperor Sapa Inka Tupac Yupanki (topaynqa yupomqui). Tupac Yupanki was the son of emperor Pachakutiq, the great Sapa Inka conqueror who made the larger four-state Inka empire.

Their names are Quechua - Yupomki might have some association with Quechua yupay-nki meaning “your Counter”). Pachacutiq can be broken down as (cutiq aka kutiy-qa, one whose return kutiy, starts a new pacha a new time/universe). Intriguingly, the spelling Guaman Poma uses, with m’s instead of n’s, implies a southern Quechua dialect, not a native Cusco dialect.

The writing on the above right “administrador suyo-yoq - apu pomachaisa? translates as”An administrator of a suyu (one of the four states of the Inca empire known as tawa-n-tin-suyu)“. Unfortunately, my modern-day Quechua skills leave me unable to translate the last line, but my guess is that here apu pomachaisa refers to the sacred place (apu) Pomacocha. Located close to the great city of Vilcashuaman, Pomacocha was regarded as an apu, likely because Tupac Yupanki was born there.It appears, to my eye, that this khipu-kamayuq is likely one of the empire’s four state-level khipu-kamayuqs - a very high official indeed. The title, clipped in the photograph, was likely COLLCA, meaning storehouse (Quechua qollqa), so this is likely a reading of goods stored at a state qollqa (indicated by all the domed buildings in the background and foreground) to the emperor at his birthplace.

1. Khipu Sources

Decipherment, Morality and the Genesis of the Harvard KDB

In 1989, using the new abilities of the computer, Oxford University Press issued its fully integrated second edition, incorporating all the changes and additions of the supplements in twenty rather more slender volumes. To help boost sales in the late seventies a two-volume set in a much-reduced typeface was issued, a powerful magnifying glass included in every slipcase. Then came a CD-ROM, and not long afterward the great work was further adapted for use on-line. A third edition, with a vast budget, was in the works.

There is some occasional carping that the work reflects an elitist, male, British, Victorian tone. Yet even in the admission that, like so many achievements of the era, it did reflect a set of attitudes not wholly harmonic with those prevalent at the end of the twentieth century, none seem to suggest that any other dictionary has ever come close, or will ever come close, to the achievement that it offers. It was the heroic creation of a legion of interested and enthusiastic men and women of wide general knowledge and interest; and it lives on today, just as lives the language of which it rightly claims to be a portrait.

Simon Winchester - The Professor and the Madman:

A Tale of Murder, Insanity, and the Making of the Oxford English Dictionary

Like the Oxford dictionary, mentioned above, the Khipu Field Guide database is not the work of one or two people, but a group of enthusiastic khipu researchers. I’d like to call out the many people who measured and created the first digital records of these khipus. However, first, I need to preface with a discussion about “data sources” and morality.

The field of epigraphy/decipherment has many stories of “esteemed” scholars behaving badly. An example from history involves the decipherment of the Maya script. In the early 20th century, scholars were aware of the existence of the Maya script, but no one had been able to decipher it. In the 1950s, a Russian scholar named Yuri Knorosov began to make progress in deciphering the script, using a combination of linguistic analysis and comparisons to known Maya inscriptions. Knorosov’s work was not immediately recognized by the Western academic establishment, in part because he was a communist and his work was seen as potentially supporting Soviet claims to influence in Central America. Meanwhile, a British scholar named Eric Thompson had been working on the Maya script for years but had made little progress.

Thompson, who was widely respected in the academic community, was determined to maintain his position as the leading Maya scholar, and he began to systematically undermine Knorosov’s work. Eventually, Knorosov’s decipherment of the Maya script was widely accepted, and Thompson’s prejudices were disposed of. However, Thompson’s actions had delayed the recognition of Knorosov’s work and contributed to a climate of mistrust and fear in the academic community. The pursuit of decipherment seems to breed personal ambition and political considerations that influence the interpretation of historical evidence. For me, Thompson’s lesson is to reemphasize the importance of integrity and accuracy in the pursuit of archaeological knowledge.

Pride, politics and citizenship are not the only biases. There is also gender. The 20th century architect Michael Ventris, who cracked ‘Linear B’, built his own work on “the unsung heroine Alice Kober.” Sadly, the khipu field, has recent, similar parallels. In this respect, the external question has been raised, should I be using khipu measurements based on a khipu measurer’s morality? Like the Oxford dictionary, some of the the Khipu Field Guide database comes from a professor who did not reflect a set of attitudes wholly harmonic with those prevalent at the end of the twentieth century. Nonetheless, the khipus exist, as do the legion of interested and enthusiastic women and men of wide general knowledge and interest. In this discussion of data sources and morality, I have been guided by the philosopher/ethicist Erich Hatala Matthes. In his book Drawing the Line: What to Do with the Work of Immoral Artists from Museums to the Movies, Matthes explores the issues of intrinsic and extrinsic values of a creator’s work and shows how ethically nuanced and careful we have to be, should we decide to:

a.) Choose to morally criticize an artefact

b.) Choose to consider the artefact maker’s morality, and

c.) Choose to prescribe how we should view or not view the artefact.

Each of these choices implies an ethical choice with many Socratic contradictions, and Matthes does his philosopher’s best to question every seemingly simple judgement about the willingness to choose to morally criticize.

One school of thought is that just as a Jackson Pollock drip painting has no evil intent, in situ, neither do khipu measurements. This school of thought says that canceling the khipu seems like an odd choice. Another school of thought says the artefact’s intent is only morally bad if you know the maker’s intent is morally bad. If you didn’t know what an arrowhead was used for, and only later discover it killed not a deer, but a baby, would you cancel your archaeological research? Another probe questions how morality changes over time. Would you cancel research into Greek pottery because it depicted homoerotic scenes? How about 100 years ago? In the future, will this work be criticized because I was a fossil-fuel climate-change inducing American? Matthes raises many of these Socratic questions.

In the end, I have chosen the Serenity Prayer - God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change; the courage to change the things I can; and the wisdom to know the difference. In this approach, the prayer’s writer independently arrived at the same conclusion as Matthes - accept there was complicity, but choose a path forward using solidarity, with transparency and the courage to change the things I can:

- Attribution and recognition of the original authors/measurers of khipus, in line with scientific convention. This includes the work of Marcia and Robert Ascher, Carrie Brezine, and Kylie Quave.

- Restoration of evanescent khipus (khipus attributed as “being present and accounted for”, when in fact the data was absent), such as the work of Kylie Quave.

- Restoration, typesetting, etc. of Ascher’s, Quave’s, etc. fieldnotes, which are as important as the khipu measurements themselves.

- Reassertion of the importance of the work of Marcia Ascher’s khipu mathematics.

As for the wisdom to know the difference? I plead human.

Finally, a cautionary note about decipherment. I mentioned British architect and amateur linguist Michael Ventris and the Linear B script above. After years of study, Ventris became convinced that Linear B was an early form of Greek. This proved to be true, and was a major breakthrough in our understanding of ancient Greek civilization and language. However, the decipherment of Linear B also had unforeseen consequences. Having the language be “Greek” radically overturned a standard picture of the prehistoric Aegean in the second millennium BC — and one standard view of when, where, and how Greek speakers arrived on the scene. The implication of Ventris’s interpretation, in other words, went far beyond anything to do with how many cattle the Minoans had, or jars of olive oil they had collected. Instead it called into question the separateness and identities of the Minoans of Crete and the Mycenaeans of the mainland. Like the decipherment of our DNA to determine our ancestry, it is not surprising that people might be reluctant to face, just on the basis of an ambitious piece of decipherment of some receipts written on clay tablets, that they are not who they thought they were. Decipherment can have profound and unexpected consequences, and it often challenges long-held assumptions and beliefs.

Data Sources for the Khipu Field Guide (KFG)

The acronym KFG refers to this Khipu Field Guide database. Some of the KFG database was derived from data in the Harvard Khipu Database, often referred to as the KDB, a collection of khipu measurements from various authors, cataloged, and then converted into Excel files and a subsequent SQL database. Consequently, it is important to note this: The Khipu Field Guide (KFG) database is not a copy of the Harvard KDB. Although some data in the KFG is extracted from the KDB,and then vetted, cleansed and normalized, the KFG is a larger collection of khipu measurements and reference information, created from multiple sources, including:

- The Harvard Khipu Database (KDB) - The Harvard KDB builds about half of its khipus from external sources such as Marcia Ascher’s Databooks, Hugo Pereyra’s publications, etc., The other half comes from the individual measurements, via Excel files and SQL tables, of both Gary Urton and Carrie Brezine. In total, their catalog provides the source material for approximately 490 khipus. This data requires considerable amounts of both programmatic and by-hand data-cleansing to be drawable. Approximately 20% of the khipus in the KDB are so malformed or incomplete, that they are unable to be used for further study - resulting in a loss of over 135 khipus from the original 623 nontrivial khipus in the KDB. As will be seen, many of those lost will be subsequently restored, either from the original author’s source or a combination of sources. Subsequent error-checking and data repair of the 490 resulted in about 50% (~250) of the khipus being hand-edited. At present, ~250 khipus (< 50%) in the KFG database, are structurally sourced from the Harvard KDB.

- Journal articles and publications (Ascher) Marcia Ascher published her khipus in two forms, her databooks, and journal articles. The KFG includes KH0002-009 from the Ascher’s publication and databook notes. From their databooks, I transcribed, and reformatted/typeset approximately 230 of Marcia and Robert Ascher’s detailed notes on their khipus into math-ready equations and text. This added a substantial amounts of contextual information, and guides for further research. Ascher’s khipus contained in the KDB have been assembled from her databooks, published articles, and from the KDB. Much modification had to be done to the KDB entries, based on information in the databooks to create a complete, well-formed set of khipus.

- Researcher’s own Excel spreadsheets:

- 2 previously unpublished khipus measured by Urton found by Mack FitzPatrick at Dumbarton Oaks.

- 22 previously unpublished khipus measured by Manuel Medrano.

- 25 previously unpublished khipus measured by Kylie Quave. Although the KDB claims to have entered all of Kylie Quave’s initial 22 khipus, only 3 are actually reasonably correct. 16 are so malformed and truncated that they are useless. 6 are new, and only in the Khipu Field Guide. I am grateful that Kylie Quave’s original Excel files could be obtained, so that her work can be recognized properly.

- 19 spreadsheets compiled from various sources, by hand, by Ashok Khosla, to reassemble malformed Pereyra and Urton khipus.

- 2 spreadsheets compiled by Sabine Hyland.

- 3 spreadsheets compiled by Karen Thompson, Saoirse Byrne, William Scannell, Di Hu & and Ashok Khosla

- 1 spreadsheet compiled by Karen Thompson of Bat-Ami Artzi’s notes and recordings of a khipu in the Maiman collection

- 1 spreadsheet compiled by Karen Thompson at the Herrett Art and Science Museum, College of Southern Idaho, Twin Falls.

- Jon Clindaniel’s Ph.D thesis at Harvard - Excel files used in reassembling ~80 malformed khipus in the KDB. Dr. Clindaniel’s files contain data not available in either the publicly available Harvard KDB, in either SQL or Excel form. While the data doesn’t show all of a khipu’s information, primary cord information, missing groups, notes, etc., it does have enough to allow a reasonable khipu reconstruction, when augmented by other data. All of Dr. Clindaniel’s 23 khipus (KH0608-KH06093) had been malformed in the Harvard SQL KDB, and thus unconstructable.

- The Open Khipu Repository.The OKR, as it’s known, is a database that descended from the Harvard KDB. It has a new decolonial modernization of khipu naming where khipus are named sequentially upon discovery. Where possible, this new OKR name is mentioned in the tables and on individual khipu pages. However, I am used to the information value that hierarchical/set naming schemes bring (ie. Linnean taxonomy, URLs, etc.) the sequential OKR naming scheme has too many issues for me to adopt it as the primary identifier - it’s inflexible (the sequential naming scheme denies insertion), it’s not open (I can’t add new khipus to it), it’s not mnemonic, and it makes reading the history of the last 50 years of khipu harder. Consequently, due to the easier identification and comprehension of the traditional two letter naming scheme, and the fifty years of khipu literature using the old naming scheme, I have kept the old naming scheme as the primary identifier, but added the OKR name as a sidebar, whenever possible.

Alas, there is one more complication with this statement.

Manuel Medrano, identified (using the museum shoe leather approach) that 15 of the khipus in the Harvard KDB are duplicates. Additionally, Karen Thompson, using pictures, identified that KH0483 is a duplicate of KH0483. At present, this list includes:

| # | Most Recent Measurement | Older Measurement | Merged Modern Name |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | KH0080 | KH0080/MA29 | KH0080 |

| 2 | KH0058 (Missing from KFG) | KH0058 | KH0058 |

| 3 | KH0049 | KH0049 | KH0049 |

| 4 | KH0057 | KH0057 | KH0057 |

| 5 | KH0099 | KH0099 | KH0099 |

| 6 | KH0083 | KH0083 | KH0083 |

| 7 | KH0032 | KH0032 | KH0032 |

| 8 | KH0033 | KH0033, KH0033 | KH0033 |

| 9 | KH0228 | KH0228 | KH0228 |

| 10 | KH0351 | KH0351 | KH0351 |

| 11 | KH0268 | KH0268 | KH0267 |

| 12 | KH0067 | KH0067 | KH0067 |

| 13 | KH0001 | LL01 | KH0001 |

| 14 | KH0198 | KH0198 | KH0198 |

| 15 | KH0483 | KH0483 | KH0198 |

| 16 | KH0081 | KH0081 | KH0081 |

As you can see many of these are Ascher khipus remeasured by Gary Urton, or Hugo Pereyra. In a few cases they are measurements of khipu by Urton, that were already measured by Urton. Want some similarity match tests? Here you go!

Textual information (chiefly Ascher notes on Ascher khipus plus measurement notes on Urton khipus) are merged into new khipus using using a modern names as suggested by the OKR, shown above. This new naming scheme does not diminish the original authors contributions, except for Urton whose contributions diminish by 3.

Again, since no one source is sufficient, the Khipu Field Guide (KFG) has used multiple sources to assemble it’s own database. Some khipus have had to rely on multiple sources such as the Harvard KDB, AND the Ascher databooks, AND the Excel spreadsheets to completely assemble one khipu correctly. From these numerous sources, the KhipuFieldGuide team has scraped, reconciled, cross-referenced, and assembled 703, useful, non-trivial khipus.the Khipu Field Guide Database is now the world’s largest well-formed khipu database.

We need to stress the phrase well-formed. To draw khipus, first, the khipu data has to hang together. Cord groups have to have the right cords. Cords have to have the right knots, etc. This requirement, that the database have “referential” integrity, so that it can be properly drawn tests the quality of the database data, and immediately makes errors visually apparent (or not visible if it’s that kind of error!). Consequently, much work in the KFG database was in resolving khipus so that they had referential integrity as well as accuracy at a given level such as knots, cords, etc. Secondly, the khipu has to have interesting data - a primary cord is not enough.

2. Who are the Counters of the Counters?

This then, is the Current Count of Counters upon whose shoulders the Khipu Field Guide now stands:

There are, at present, 703 unique, well formed khipus. The original authors of these khipus are:

- Gary Urton - (238 khipus) These khipus were assembled from the KDB, Jon Clindaniel’s Excel files. Most of these files required further modifications and corrections to allow them to be analyzed and drawn. An additional two files were obtained by Mack FitzPatrick, who found a series of handwritten looseleaf sheets at Dumbarton Oaks, containg the data for KH0674 and KH0675.

- Marcia Ascher - (229 khipus) Approximately 80 khipus first studied by the Aschers, were relabeled as Urton khipus by Urton. This action disregards scientific convention. I mention the original author, as a partial remedy, in the drawings.

- Carrie Brezine - (61 khipus) Although labeled as Urton khipus, according to the Harvard KDB, 61 of the khipus were measured by Carrie Brezine. Again, to remedy this disregard for convention, I have mentioned the original author in the drawings.

- Hugo Pereyra - (56 khipus) Assembled from a combination of the Harvard KDB, which was assembled from Pereyra’s publication and Jon Clindaniel’s Excel files to fix malformed khipus.

- Jon Clindaniel - (23 khipus) Assembled from Jon Clindaniel’s Excel files to to obtain cord information and the Harvard KDB to obtain cord group information.

- Manuel Medrano - (22 khipus) Assembled from Manuel Medrano’s previously unpublished Excel files.

- Kylie Quave - (25 khipus) Assembled from Kylie Quave’s previously unpublished Excel files.

- Sabine Hyland - (2 khipus) Assembled from Sabine Hyland’s previously unpublished Excel files.

- Karen Thompson, Saoirse Byrne, Di Hu & Ashok Khosla - (3 khipus) Assembled from KFG Affliate measurements of three khipus from the Maiman collection.

- Karen Thompson - (1 khipu) Assembled from Karen Thompson’s visit to the Herrett Art and Science Museum, College of Southern Idaho, Twin Falls.

- Leland Locke - (1 khipu) Assembled from the Harvard KDB.

- Carol Mackey - (1 khipu) Reconstructed from her 1970 Doctoral Thesis

3. Yak-Shaving: Assembling The Khipu Database

3.1 The Harvard Khipu SQL Database

Prior to Urton’s banishment from Harvard, the Harvard KDB was easily obtained from the Harvard Khipu Database project. The khipu data was in two forms - a limited set of 349 khipus in Excel and a bigger SQL database of about 625+ khipu. I chose the larger database, a territory largely untraveled. So the steps were to:

- Gather the data. In this case I started with the SQL data due to the larger data set size.

- Cleanse/check the data . This is where it always gets hairy. I was unable to find any code that dealt with the SQL database directly. So I got the arrows in the back of virgin territory. The data fails in various ways. It took me a while to discover the many, many issues. From khipus with no cords, to khipus with no knots, to khipus with cords that didn’t exist, or belong to another khipu, to not knot’s that don’t exist, it’s been a fascinating Zen journey in the perils of data integrity. When crossing the bridge from archaeology to computation, I’ve learned it takes ENORMOUS amounts of data checking and time.

Along the journey, one night, tired and frustrated with data integrity checks, I saw a note in the cord database nudo desanudado. Unknotted knot. That’s what this cleansing has been like.

In the end, the Harvard Khipu Database, yielded about 490 khipu that could serve as the starting point for a database. By back-filling from the original Harvard Excel files and Jon Clindaniel’s thesis files, I was able to reassemble another approximately 80 malformed khipus. An additional 19 khipus were assembled by hand from several sources and restored, by me, into “whole” khipus. Import of Kylie Quave’s khipus, extracted from her original Excel spreadsheets, completely replaced 16 khipus that were, in fact, empty, restored 3 partial khipus, and added 3 new khipus. Numerous errors in the KDB khipus were repaired - resulting in changes to over 200 Harvard KDB khipus, with errors such as bad cord lengths, reversed cord/cord group order, incorrect cord group sequences, oddly named pendants, malformed subsidiaries, etc. were repaired by hand as a result of an error-checker failing, or the drawing failing.

The effort to build the initial starting point of Khipu Field Guide’s database from the Harvard KDB was long and gnarly (that’s not an Academic word, but its use in Industry is appropriate here LOL). If you enjoy reading about pain and suffering feel free to read the documentation.

3.2 Excel

Before SQL, there was Excel. Many of the original files were collected and documented in Microsoft Excel. When I added the Ascher’s KH0002-KH0010 khipus, I used Excel. Eventually, I used Excel for everything. So, it turns out does almost everyone else. Although SQL scales, it’s monolithic approach makes update and additions difficult, and frankly, intimidating to the nonSQL. Althoug I’ve had a long career in Silicon Valley, including addressing large database scalability issues, I ended up having a loathing for SQL as a research vehicle. When I had to invent new khipus to solve a research problem, the process of SQL updates took a looong week instead of a short day to get the prototypes correct. At that point, I realized it was best to give up on SQL and start anew.

Version 2 of the database, after 4 years of SQL hacking, is built entirely on Excel files. Each Excel file is read by a python program, which then creates a python “pickle” file (a binary representation of the python object) of the object-oriented Python Khipu class. From then on, the database is simply read into memory, as needed. Between the speed of Python object pickles, and the fact that we only have ~700 khipus not 65000, I have given up on SQL, in this second incarnation of the Khipu FieldGuide database. The database is now a set of files in a standardized Excel Format. These datafiles are downloadable on their respective khipu information webpage. The entire database, consumes 26Mbytes of memory, gigantic, at the time the Harvard KDB was created, and PCs had 640kb, but a microscule amount of data in the 21st century.

Having each khipu have it’s own Excel file allows easy data-checking and rapid iteration on the data. Numerous data recording errors have been subsequently revealed and fixed in this manner.

As mentioned before, these author’s files were provided in some form of Excel and added to the database via conversion to the standard KFG Excel format.

3.3 Original Historical Sources

After deciding, in 2023, that Excel would became the normative form of literate storage, it became easier to enlist others in adding khipus to the database, and for other scholars to mine the original sources and compare them with the present Excel files. This effort, led by Karen Thompson , has resulted in numerous repairs and alterations to the Ascher Khipus, based on data contained in their Databooks and in numerous repairs and alterations to the Hugo Peyrera khipus based on similar original sources.

4. KFG Database Completeness

Now that we have a database of khipus, it’s a good time to review how complete the data is. For example, how many khipus have cords with knots, with known colors, etc. The current list of data to inventory includes:

- Number of Cords (including pendants, top cords, subsidiaries)

- Number of Pendant Cords (not including top cords)

- Number of Top Cords

- Number of Subsidiaries

- Cords With Known Colors

- Cords with Known Cord Ply/Spin

- Cords with Known Cord Attachments

- Number of Knots

- Khipus w/at Least 1 Knot (aka Zero Knot Khipus)

- Knots with Known Twists

- Long Knots with Known Axis Orientation (for Long Knots)

Let’s evaluate each of these in turn. We’ll look only at Pendants for now in interests of making the search easier. Similarly, we’ll only list the number of khipus that have at least some data.

4.1 Number of Cords (including pendants, top cords, subsidiaries)

Code

num_corded_khipus = sum([aKhipu.num_all_cords() > 0 for aKhipu in all_khipus])

corded_khipus = [aKhipu for aKhipu in all_khipus]

num_cords = sum([aKhipu.num_all_cords() for aKhipu in all_khipus])

num_pendants = sum([aKhipu.num_pendant_cords() for aKhipu in all_khipus])

print(f"Number of khipus with cords = {num_corded_khipus}")

print(f"Number of all cords (including top cords and subsidiaries) = {num_cords}")

print(f"Number of pendant cords (including top cords) = {num_pendants}")Number of khipus with cords = 668

Number of all cords (including top cords and subsidiaries) = 60858

Number of pendant cords (including top cords) = 439364.2 Number of Pendant Cords (not including top cords)

4.3 Number of Top Cords

4.4 Number of Subsidiaries

4.5 Khipus with No Colors

How many khipus have not measured their colors?

Code

no_color_khipus = []

def has_no_color(aCord):

return aCord.main_color()=="PK" or aCord.main_color() == ""

no_color_khipus = []

for aKhipu in all_khipus:

if all([has_no_color(aCord) for aCord in aKhipu.all_cords()]):

no_color_khipus.append(aKhipu.name())

print(f"# of Khipus with No Known Color is {len(no_color_khipus)}")

khipu_rep = uloom.multiline(no_color_khipus, continuation_char="\n ")

print(f"No Color Khipus =\n{khipu_rep}")# of Khipus with No Known Color is 3

No Color Khipus =

['AS072', 'AS073', 'AS187']4.6 Khipus with No Known Cord Ply/Spin

Code

khipus_by_cord_ply = {aKhipu.kfg_name():0 for aKhipu in all_khipus}

for aKhipu in all_khipus:

if num_khipu_cords := aKhipu.num_all_cords():

khipus_by_cord_ply[aKhipu.kfg_name()] = (aKhipu.num_s_cords() + aKhipu.num_z_cords())/num_khipu_cords

khipus_by_cord_ply = dict(sorted(khipus_by_cord_ply.items(), key=lambda x:x[1]))

zero_cord_ply_khipus = [key for key in khipus_by_cord_ply.keys() if khipus_by_cord_ply[key]==0 ]

num_zero_cord_ply_khipus = len(zero_cord_ply_khipus)

print(f"# of Khipus with No Known Cord Ply/Spin is {num_zero_cord_ply_khipus}")

khipu_rep = uloom.multiline(zero_cord_ply_khipus, line_length=80, continuation_char="\n ")

print(f"Zero Cord Ply Khipus =\n{khipu_rep}")# of Khipus with No Known Cord Ply/Spin is 140

Zero Cord Ply Khipus =

['AS001', 'AS002', 'AS003', 'AS004', 'AS005', 'AS006', 'AS007', 'AS008',

'AS009', 'AS010', 'AS011', 'AS012', 'AS013', 'AS014', 'AS015', 'AS016', 'AS017',

'AS018', 'AS019', 'AS020', 'AS021', 'AS022', 'AS023', 'AS024', 'AS025',

'AS026A', 'AS026B', 'AS027', 'AS028', 'AS029', 'AS35A', 'AS35B', 'AS035C',

'AS035D', 'AS036', 'AS037', 'AS039', 'AS041', 'AS042', 'AS043', 'AS044',

'AS045', 'AS048', 'AS050', 'AS054', 'AS055', 'AS059', 'AS060', 'AS061/MA036',

'AS062', 'AS063', 'AS063B', 'AS064', 'AS065', 'AS065B', 'AS066', 'AS069',

'AS071', 'AS072', 'AS073', 'AS077', 'AS081', 'AS082', 'AS083', 'AS085', 'AS089',

'AS090/N2', 'AS092', 'AS093', 'AS094', 'AS101 - Part 1', 'AS101 - Part 2',

'AS110', 'AS111', 'AS112', 'AS115', 'AS122', 'AS125', 'AS128', 'AS129', 'AS132',

'AS133', 'AS134', 'AS137', 'AS139', 'AS142', 'AS153', 'AS155', 'AS156', 'AS157',

'AS158', 'AS159', 'AS160', 'AS164', 'AS168', 'AS169', 'AS171', 'AS172', 'AS173',

'AS174', 'AS177', 'AS178', 'AS182', 'AS182B', 'AS183', 'AS184', 'AS185',

'AS186', 'AS187', 'AS188', 'AS189', 'AS190', 'AS201', 'AS202', 'AS203', 'AS204',

'AS205', 'AS206', 'AS207A', 'AS207B', 'AS207C', 'AS209', 'AS210', 'AS211',

'AS212', 'AS213', 'AS214', 'AS215', 'AS215F', 'CM009', 'HP052', 'KH0058',

'KH0080', 'QU025', 'UR1033A', 'UR1034', 'UR1040', 'UR1052', 'UR1127', 'UR1141']4.7 Khipus with No Known Cord Attachment

Code

khipus_by_cord_attachment = {}

for aKhipu in all_khipus:

if num_khipu_cords := aKhipu.num_pendant_cords():

khipus_by_cord_attachment[aKhipu.name()] = (aKhipu.num_top_cords() + aKhipu.num_recto_cords() + aKhipu.num_verso_cords())/num_khipu_cords

else:

khipus_by_cord_attachment[aKhipu.name()] = 0

khipus_by_cord_attachment = dict(sorted(khipus_by_cord_attachment.items(), key=lambda x:x[1]))

zero_cord_attachment_khipus = [key for key in khipus_by_cord_attachment.keys() if khipus_by_cord_attachment[key]==0 ]

num_zero_cord_attachment_khipus = len(zero_cord_attachment_khipus)

print(f"# of Khipus with No Known Cord Attachment is {num_zero_cord_attachment_khipus}")

khipu_rep = uloom.multiline(zero_cord_attachment_khipus, line_length=80, continuation_char="\n ")

print(f"Zero Cord Attachment Khipus =\n{khipu_rep}")# of Khipus with No Known Cord Attachment is 189

Zero Cord Attachment Khipus =

['AS005', 'AS009', 'AS011', 'AS012', 'AS014', 'AS015', 'AS016', 'AS017',

'AS018', 'AS019', 'AS020', 'AS022', 'AS023', 'AS024', 'AS025', 'AS026A',

'AS026B', 'AS027', 'AS028', 'AS029', 'AS35A', 'AS35B', 'AS035C', 'AS035D',

'AS036', 'AS037', 'AS039', 'AS041', 'AS042', 'AS043', 'AS045', 'AS048', 'AS050',

'AS054', 'AS055', 'AS059', 'AS060', 'AS062', 'AS063', 'AS063B', 'AS064',

'AS065', 'AS065B', 'AS069', 'AS071', 'AS073', 'AS077', 'AS081', 'AS082',

'AS083', 'AS085', 'AS089', 'AS090/N2', 'AS092', 'AS093', 'AS094', 'AS101 - Part

1', 'AS101 - Part 2', 'AS110', 'AS111', 'AS112', 'AS122', 'AS125', 'AS128',

'AS129', 'AS132', 'AS133', 'AS134', 'AS137', 'AS139', 'AS142', 'AS153', 'AS155',

'AS156', 'AS157', 'AS158', 'AS159', 'AS160', 'AS164', 'AS168', 'AS169', 'AS170',

'AS171', 'AS172', 'AS173', 'AS174', 'AS177', 'AS178', 'AS182', 'AS182B',

'AS183', 'AS184', 'AS185', 'AS186', 'AS187', 'AS188', 'AS189', 'AS190', 'AS201',

'AS202', 'AS203', 'AS204', 'AS205', 'AS206', 'AS207B', 'AS207C', 'AS209',

'AS210', 'AS211', 'AS212', 'AS213', 'AS214', 'AS215', 'AS215F', 'CM009',

'KH0058', 'QU025', 'UR040', 'UR041', 'UR042', 'UR050', 'UR051', 'UR052',

'UR054', 'UR055', 'UR084', 'UR110', 'UR112', 'UR127', 'UR129', 'UR132', 'UR144',

'UR215', 'UR1033A', 'UR1034', 'UR1040', 'UR1097', 'UR1098', 'UR1099', 'UR1100',

'UR1102', 'UR1103', 'UR1105', 'UR1106', 'UR1107', 'UR1108', 'UR1109', 'UR1113',

'UR1114', 'UR1116', 'UR1117', 'UR1118', 'UR1119', 'UR1120', 'UR1121', 'UR1123',

'UR1124', 'UR1124 Detail 1', 'UR1126', 'UR1127', 'UR1130', 'UR1131', 'UR1135',

'UR1136', 'UR1138', 'UR1140', 'UR1141', 'UR1143', 'UR1144', 'UR1145', 'UR1146',

'UR1147', 'UR1148', 'UR1149', 'UR1150', 'UR1151', 'UR1152', 'UR1154', 'UR1161',

'UR1162A', 'UR1162B', 'UR1163', 'UR1165', 'UR1166', 'UR1167', 'UR1175',

'UR1176', 'UR1179', 'UR1180']4.8 Number of Knots

4.9 Khipus with No Knots

How many Khipus have no knots?

Code

## Zero Knot Khipus

def satisfaction_condition(aCord):

return aCord.knotted_value==0

zero_knot_khipus = []

for aKhipu in all_khipus:

if all([satisfaction_condition(aCord) for aCord in aKhipu[:,:]]):

zero_knot_khipus.append(aKhipu.name())

print(f"# of Khipus with No Knots is {len(zero_knot_khipus)}")

khipu_rep = uloom.multiline(zero_knot_khipus, line_length=80, continuation_char="\n ")

print(f"Zero Knot Khipus =\n{khipu_rep}")# of Khipus with No Knots is 13

Zero Knot Khipus =

['AS190', 'HP025', 'HP026', 'HP028', 'QU001', 'UR070', 'UR071', 'UR082',

'UR103', 'UR158', 'UR179', 'UR185', 'UR216']4.10 Khipus with no Knot Twists

How many Khipus have knots with unrecorded twists?

Code

khipus_by_knot_twist = {}

for aKhipu in all_khipus:

if num_khipu_knots := aKhipu.num_knots():

khipus_by_knot_twist[aKhipu.kfg_name()] = (aKhipu.num_s_knots() + aKhipu.num_z_knots())/num_khipu_knots

else:

khipus_by_knot_twist[aKhipu.kfg_name()] = 0

khipus_by_knot_twist = dict(sorted(khipus_by_knot_twist.items(), key=lambda x:x[1]))

zero_knot_twist_khipus = [key for key in khipus_by_knot_twist.keys() if khipus_by_knot_twist[key]==0 ]

num_zero_knot_twist_khipus = len(zero_knot_twist_khipus)

print(f"# of Khipus with No Known Knot Twist is {num_zero_knot_twist_khipus}")

khipu_rep = uloom.multiline(zero_knot_twist_khipus, line_length=80, continuation_char="\n ")

print(f"No Known Knot Twist Khipus =\n{khipu_rep}")# of Khipus with No Known Knot Twist is 192

No Known Knot Twist Khipus =

['AS001', 'AS002', 'AS003', 'AS004', 'AS005', 'AS006', 'AS007', 'AS008',

'AS009', 'AS010', 'AS011', 'AS012', 'AS013', 'AS014', 'AS015', 'AS016', 'AS017',

'AS018', 'AS019', 'AS020', 'AS021', 'AS022', 'AS023', 'AS024', 'AS025',

'AS026A', 'AS026B', 'AS027', 'AS028', 'AS029', 'AS35A', 'AS35B', 'AS035C',

'AS035D', 'AS036', 'AS037', 'AS039', 'AS041', 'AS042', 'AS043', 'AS044',

'AS045', 'AS048', 'AS050', 'AS054', 'AS055', 'AS059', 'AS060', 'AS061/MA036',

'AS062', 'AS063', 'AS063B', 'AS064', 'AS065', 'AS065B', 'AS066', 'AS069',

'AS071', 'AS072', 'AS073', 'AS077', 'AS081', 'AS082', 'AS083', 'AS085', 'AS089',

'AS090/N2', 'AS092', 'AS093', 'AS094', 'AS101 - Part 1', 'AS101 - Part 2',

'AS110', 'AS111', 'AS112', 'AS115', 'AS122', 'AS125', 'AS128', 'AS129', 'AS132',

'AS133', 'AS134', 'AS137', 'AS139', 'AS142', 'AS153', 'AS155', 'AS156', 'AS157',

'AS158', 'AS159', 'AS160', 'AS164', 'AS168', 'AS169', 'AS170', 'AS171', 'AS172',

'AS173', 'AS174', 'AS177', 'AS178', 'AS182', 'AS182B', 'AS183', 'AS184',

'AS185', 'AS186', 'AS187', 'AS188', 'AS189', 'AS190', 'AS198', 'AS200', 'AS201',

'AS202', 'AS203', 'AS204', 'AS205', 'AS206', 'AS207A', 'AS207B', 'AS207C',

'AS209', 'AS210', 'AS211', 'AS212', 'AS213', 'AS214', 'AS215', 'AS215F',

'BA001', 'CM009', 'HP025', 'HP026', 'HP028', 'HP039', 'HP044', 'HP047', 'HP048',

'HP049', 'HP052', 'KH0049', 'KH0058', 'KH0080', 'KH0081', 'MM011', 'MM013',

'MM014', 'QU001', 'QU005', 'QU006', 'UR002', 'UR013', 'UR024', 'UR039', 'UR040',

'UR041', 'UR042', 'UR051', 'UR052', 'UR053D', 'UR070', 'UR071', 'UR082',

'UR098', 'UR099', 'UR100', 'UR101', 'UR108', 'UR112', 'UR121', 'UR123',

'UR131A', 'UR131C', 'UR136', 'UR137', 'UR158', 'UR216', 'UR250', 'UR263',

'UR265', 'UR290', 'UR297', 'UR1034', 'UR1040', 'UR1097', 'UR1099', 'UR1105',

'UR1116', 'UR1117']4.11 Khipus with Long Knots with Known Axis Orientation

How many Khipus record axis orientation of long knots?

Code

khipus_with_axis_orientation = []

for aKhipu in all_khipus:

if has_axis_declared := any([aKnot for aKnot in aKhipu.all_knots() if aKnot.axis_orientation]):

khipus_with_axis_orientation.append(aKhipu.kfg_name())

num_khipus_with_axis_orientation = len(khipus_with_axis_orientation)

print(f"# of Khipus with at least one knot which has axis_orientation declared is {num_khipus_with_axis_orientation}")

khipu_rep = uloom.multiline(khipus_with_axis_orientation, line_length=80, continuation_char="\n ")

print(f"Khipus with Knot Axis Orientation Declared =\n{khipu_rep}")# of Khipus with at least one knot which has axis_orientation declared is 29

Khipus with Knot Axis Orientation Declared =

['AK001', 'AK002', 'AK003', 'MM001', 'MM002', 'MM003', 'MM004', 'MM005',

'MM006/AN001', 'MM007/AN002', 'MM008', 'MM009', 'MM010', 'MM011', 'MM012',

'MM013', 'MM014', 'MM015', 'MM016', 'MM017', 'MM018', 'MM019', 'MM020', 'MM021',

'MM022', 'MM1086', 'UR221', 'UR297', 'UR298']4.12 Khipus with Broken Cords

Code

def is_broken_primary_cord(aKhipu):

return aKhipu.primary_cord.is_broken()

def num_broken_cords(aKhipu):

return sum([aCord.is_broken() for aCord in aKhipu.all_cords(include_subsidiaries=True, include_top_cords=True)])

khipus_with_broken_primaries = [aKhipu for aKhipu in all_khipus if is_broken_primary_cord(aKhipu)]

khipus_with_broken_cords = [(aKhipu.kfg_name(), num_broken_cords(aKhipu)) for aKhipu in all_khipus if num_broken_cords(aKhipu)>0]

num_all_cords = sum([aKhipu.num_all_cords() for aKhipu in all_khipus])

num_broken_cords = sum([the_num_broken_cords for (_, the_num_broken_cords) in khipus_with_broken_cords])

print(f"{uloom.percent_info(len(khipus_with_broken_primaries), len(all_khipus))} of khipus have broken primaries")

print(f"{uloom.percent_info(len(khipus_with_broken_cords), len(all_khipus))} of khipus have broken cords")

print(f"{uloom.percent_info(num_broken_cords, num_all_cords)} of All cords are Broken")25% (166 of 668) of khipus have broken primaries

80% (534 of 668) of khipus have broken cords

20% (12412 of 60858) of All cords are Broken4.13 Canuto Khipus

Canuto khipus are defined as khipus with at least 50% of the cords having 2 or more long knots.

4.14 Non-Lockean Cords

Lockean knot typology is considered the “normal” cord typology. This is a cord which must follow one of the following conditions:

- It has no knots (cord value = 0)

- It has only single knots (cord value = sum of knot values*register)

- It has one long knot (cord value = = 1*number of long knot turns)

- It has all single knots and 1 long knot at the end (cord value = sum of knot values*register)

Code

def not_lockean_knot_typology(aCord):

""" A lockean cord contains none, or only S, and L knots and if an L occcurs, it is the last knot and only has one instance """

all_knots = aCord.all_knots(include_subsidiaries=False)

is_lockean = len(all_knots) == 0 # No knots

if not is_lockean: # All Single Knots

is_lockean = all([aKnot.is_single_knot() for aKnot in all_knots])

if not is_lockean: # Last knot is an L knot

is_lockean = all_knots[-1].is_generalized_long_knot()

if len(all_knots) > 1: # Previous knots must be single knots

is_lockean = is_lockean and all(aKnot.is_single_knot() for aKnot in all_knots[:-1])

return not is_lockean

def calc_non_lockean_cords():

non_lockean_khipus_dict = ukhipu.find_KFG_cords(not_lockean_knot_typology)

non_lockean_khipus_dict = {kfg_name:len(cord_list) for kfg_name, cord_list in non_lockean_khipus_dict.items() if (len(cord_list) > 0)}

return uloom.sort_dict_by_values(non_lockean_khipus_dict)

print(f"{uloom.percent_info(len(calc_non_lockean_cords()), len(all_khipus))} Khipus have a Cord with a Non-Lockean Knot Typology")

num_all_cords = sum([aKhipu.num_all_cords() for aKhipu in all_khipus])

num_non_lockean_knot_cords = sum(calc_non_lockean_cords().values())

print(f"{uloom.percent_info(num_non_lockean_knot_cords, num_all_cords)} of All Cords Have a Non-Lockean Knot Typology")

print("\nTop 25 Khipus with Non-Lockean Knot Typology by Number of Non-Lockean Cords:")

for index, (khipu_name, num_nether_knot_cords) in enumerate(calc_non_lockean_cords().items()):

if index < 25:

print(f'{index+1}: {khipu_name}: {num_nether_knot_cords}')

80% (535 of 668) Khipus have a Cord with a Non-Lockean Knot Typology

12% (7306 of 60858) of All Cords Have a Non-Lockean Knot Typology

Top 25 Khipus with Non-Lockean Knot Typology by Number of Non-Lockean Cords:

1: UR055: 173

2: UR087: 165

3: UR050: 164

4: UR283: 128

5: UR006: 127

6: UR054: 113

7: UR1057: 109

8: UR004: 102

9: UR093: 95

10: UR052: 92

11: UR1032: 91

12: UR1095: 90

13: UR198: 88

14: UR193: 84

15: UR211: 83

16: UR278: 83

17: UR003: 79

18: UR203: 77

19: UR051: 75

20: UR021: 74

21: UR001: 72

22: UR113: 72

23: KH0001: 69

24: UR039: 67

25: QU024: 654.15 Nether Knot Khipus

Sabine Hyland, in her article Knot Anomalies on Inka Khipus: Revising Locke’s Knot Typology - DOI: 10.32873/unl.dc.zea.1617 Published in IX Jornadas Internacionales de Textiles Precolombinos y Amerindianos / 9th International Conference on Pre-Columbian and Amerindian Textiles, Museo delle Culture, Milan, 2022. (Lincoln, Nebraska: Zea Books, 2024) describes an attempt to make unconventional lockean knot sequences such as SSLL with multiple finishing Long Knots or other anomalous end-knot sequences. She refers to these anomalous end knots as “nether knots” and suspects that these should be Subtracted rather than added to the cord value - which is the current convention.

Code

##################################################################################--

# SAMPLE CODE EXTRACTED FROM KFG source

##################################################################################--

# See Sabine Hyland's article on Nether Knots

# Knot Anomalies on Inka Khipus: Revising Locke’s Knot Typology

# DOI: 10.32873/unl.dc.zea.1617

# Published in IX Jornadas Internacionales de Textiles Precolombinos y Amerindianos

# 9th International Conference on Pre-Columbian and Amerindian Textiles, Museo delle Culture, Milan, 2022. (Lincoln, Nebraska: Zea Books, 2024)

def nether_knots(aCord):

""" Returns [possibly empty] list of nether knots - knots that are below the first long knot """

the_nether_knots = []

all_knots = aCord.all_knots(include_subsidiaries=False)

long_knot_index = uloom.find_first_index(all_knots, lambda aKnot: aKnot.is_generalized_long_knot())

if not (long_knot_index is None):

the_nether_knots = all_knots[long_knot_index+1:]

# An example of why this may be useful. Some cords have 1 long, 1 long, 1 long, 1 long knot (total of 4)

# If the last 3 knots are nether knots, then the subtract value approach shouldn't apply and result should be 4

if all([aKnot.value == 1 for aKnot in all_knots]): the_nether_knots = []

return the_nether_knots

def has_nether_knots(aCord):

return len(aCord.nether_knots()) > 0Code

def has_nether_knot(aCord):

return aCord.has_nether_knots()

def get_nether_knots():

all_khipus_dict = ukhipu.find_KFG_cords(has_nether_knot)

nether_cords_dict = {kfg_name:len(cord_list) for kfg_name, cord_list in all_khipus_dict.items() if (len(cord_list) > 0) and (not khipu_dict[kfg_name].is_canuto_khipu())}

return uloom.sort_dict_by_values(nether_cords_dict)

print(f"{uloom.percent_info(len(get_nether_knots()), len(all_khipus))} Khipus have a Nether Knot Cord")

num_all_cords = sum([aKhipu.num_all_cords() for aKhipu in all_khipus])

num_nether_knot_cords = sum(get_nether_knots().values())

print(f"{uloom.percent_info(num_nether_knot_cords, num_all_cords)} of All Cords Have Nether Knot Cords")

print("\nTop 25 Khipus with Nether Knots by Number of Nether Knots Cords:")

for index, (khipu_name, num_nether_knot_cords) in enumerate(get_nether_knots().items()):

if index < 25:

print(f'{index+1}: {khipu_name}: {num_nether_knot_cords}')34% (230 of 668) Khipus have a Nether Knot Cord

2% (1411 of 60858) of All Cords Have Nether Knot Cords

Top 25 Khipus with Nether Knots by Number of Nether Knots Cords:

1: UR193: 84

2: KH0001: 69

3: UR1095: 54

4: UR203: 52

5: UR278: 42

6: UR1087: 42

7: AS090/N2: 37

8: UR112: 37

9: AS014: 31

10: UR277: 27

11: MM019: 26

12: UR283: 25

13: AS069: 22

14: AS026B: 21

15: KT001: 21

16: UR268: 20

17: UR270: 20

18: UR269: 19

19: UR037: 18

20: UR177: 17

21: UR1145: 17

22: UR272: 16

23: UR196: 15

24: UR267B: 15

25: UR267A: 144.16 Database (In)Completeness

Summary of Database (In)Completeness

| Feature | % of All Cords | # of Khipus | Percentage |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broken Cords | 20% | 530 | 80% |

| Non-Lockean Knot Typology Cords | 12% | 531 | 80% |

| Nether Knot Cords | 3% | 229 | 34% |

| No Known Knot Twist | 188 | 28% | |

| Broken Primaries | 163 | 25% | |

| No Known Cord Ply/Spin | 136 | 20% | |

| At least 1 knot Axis Orientation Declared | 24 | 3.6% | |

| Duplicate Khipus (Removed) | 15 | 2.3% | |

| No Knots | 14 | 2.1% | |

| Canuto Khipus | 8 | 1.2% | |

| No Known Cord Attachment | 4 | 0.6% | |

| No Known Color | 3 | 0.5% |